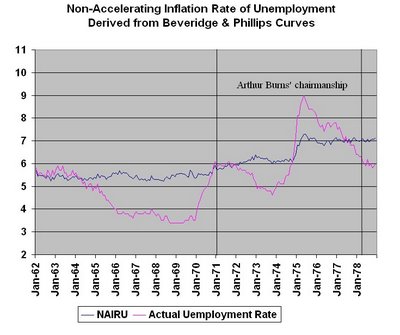

Already, I realize I’m going to have to start spacing out my NAIRU posts, or I’ll have to change the name of this blog to “NAIRU and…” But the NAIRU wars

continue, and this is a good time for my first substantive post on the subject.

In my first reply to Angelica (Battlepanda) in the comments to the link above, I conclude:

But eventually, at some point, you will have to raise interest rates. How do you determine that point, and why? Whatever answer you give will imply some theory about the way the world works, and it may or may not be a better theory than the NAIRU. If we don’t know what the theory is, though, we’ll probably never know if it’s a better theory.

Here I will suggest and comment on some possible alternatives, to argue (briefly) why I think they are not sufficient to make the NAIRU theory obsolete:

1.

intuition.

First of all, this is a nice trick if you can do it. If you can clone Alan Greenspan

ad infinitum, we’ll probably be fine. Otherwise, I’m not so sure. Among ordinary mortals, intuition can be severely clouded, for example, when the man who appointed you is a corrupt megalomaniac who thinks the future of the free world depends on his being reelected.

Second of all, “intuition” really begs the question. “Intuition” means either that you have a theory you don’t know how to express (or can’t explain why you believe), or that you have several theories you are weighing in your mind. In Greenspan’s case it was maybe a little of both. Though Greenspan publicly disavowed the starkest version of the NAIRU theory, there was surely some version of the theory in the witch’s brew of theories that informed his intuitive decisions. And the Fed’s course in the late 90s seems pretty close to optimal (at least if you don’t think they should worry about asset bubbles). If Larry Meyer and his fellow NAIRU advocates hadn’t been there to toss in some eye of newt, the brew might not have had the right effect.

2.

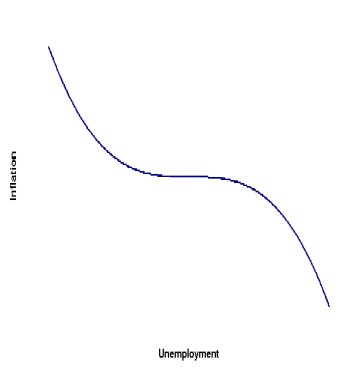

downward-sloping long-run Phillips curveThis is the theory that prevailed before the NAIRU unseated it. Personally, I think economists were too hasty to reject it. The inflation of the 1970s provided a strong emotional argument against the old theory, but the inflation had various other contributing causes (e.g., OPEC, a tumultuous labor market, a corrupt megalomaniac working with an intuitive Fed chairman) besides a possibly bad theory that might have distorted policy. But good luck trying to convince just about any other living economist today to resurrect the old Phillips curve! It’s like trying to sell whiskey to a Salvation Army general.

3.

privatized monetary policy The Austrian school argues (IIRC) that we should get rid of the Fed altogether and let banks create their own money, secured by the credibility of their promise to pay in gold (or in something else of value). This is a really bad idea. Don’t even get me started.

4.

monetary aggregate targetingBeen there. Done that. The results weren’t pretty. And that was before the last 20 years of financial innovations, which have further softened the links between nominal income and the money supply. Like the downward-sloping long-run Phillips curve, this is an idea that has been tried and rejected, but in this case I agree with the consensus. (By the way, anyone who is familiar with the career of Milton Friedman will see a certain irony in proposing monetary aggregate targeting as an

alternative to the NAIRU theory.)

5.

real business cycle theoryI doubt that anyone who reads this blog will seriously suggest using this as a primary guide to policy, but I include it because it’s still the most academically respectable alternative to the NAIRU. If anyone does think this is the way to go, I’d be interested to hear details.

6.

commodity targetingThis is what supply-siders tend to like, but I notice they tend to change their minds about which commodities to target depending on what policy implications suit their current fancy. I think it’s a very bad idea anyhow. Over the last few years, for example, various commodity prices have been rising rapidly. If our currency were tied to those commodities, we would be contracting the money supply and deflating the rest of the economy. Of course, we could have chosen commodities that don’t happen to be rising now, but then some other day we’ll have the same problem. (And if we’re allowed repeatedly to change which commodities to target, then this is no policy at all.)

7.

Taylor rule without an output termIn other words, raise interest rates when the inflation rate goes up, and get more aggressive the more it goes up. I guess this is the most obvious, and the most widely acceptable, alternative.

But it’s a dumb idea. Implicitly, it’s based on a theory that is even dumber than the NAIRU theory: namely, that next year’s inflation rate equals this year’s inflation rate (plus some completely unpredictable random change). The implication is that economists who forecast inflation have been complete failures and should be replaced by someone who just copies a number from one spreadsheet cell to another. That’s just not true: while they haven’t done nearly as well as one might hope, they haven’t completely failed.

There is plenty of information (the unemployment rate being the most obvious example) that can help forecast inflation, and the Fed should take advantage of that information. For Heaven’s sake, if the unemployment rate goes down to 3%, I don’t care if you see any new inflation

yet; you’ve gotta raise interest rates! And if it goes up to 9%, I don’t care if you don’t see the inflation rate falling yet; you’ve gotta cut interest rates!

8.

any other ideas?I have some that I like, but that’s for another post. (And I’m really talking about ideas derived from the NAIRU theory, anyhow.)

UPDATE: OK, I was a little unfair to the Taylor rule (7). Obviously there has to be some feedback from monetary policy to inflation; otherwise nothing the Fed did would have any effect. So the implied theory is not quite as degenerate as I suggested. However, it is essentially saying that the process by which monetary policy affects the inflation rate is a “black box,” the contents of which we know nothing about. That’s just silly.

Labels: economics, inflation, macroeconomics, NAIRU, Phillips curve, unemployment