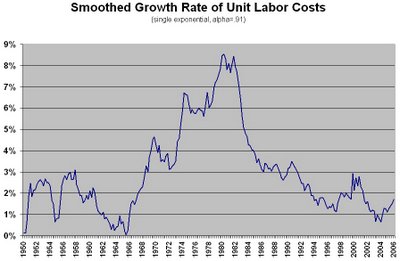

Take another look at

this picture. Something screwy is going on. Labor costs have risen at an average rate of 1.5% over the past 15 years, but prices have risen at an average rate of more than 2%. That means labor is really cheap today compared to what it was 15 years ago. Why isn’t somebody hiring that cheap labor and undercutting competitors by charging lower prices (bringing down the rate of price growth, or bringing up the rate of labor cost growth by bidding more for labor)? I consider several explanations, but none seems quite satisfactory.

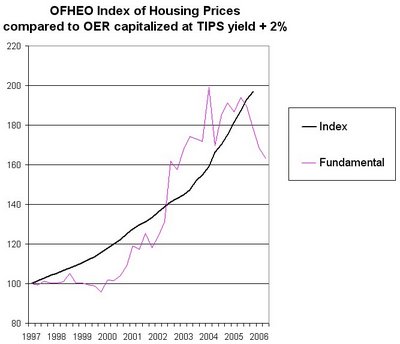

1. Rising raw material prices. If the cost of non-labor inputs is going up, then firms could be forced to raise prices even when labor is cheap. When you look at oil prices today, this seems like a good explanation, but take a look at

this chart, which Barry Ritholtz found in a St. Louis Fed publication. Profits have risen dramatically as a share of national income, while compensation has fallen. If raw materials costs were the problem, we would expect them to be cutting into profits. Clearly they’re not, at least not in aggregate.

2. Increasing cost of capital. When economists talk about the “zero profit condition,” they are careful to distinguish economic profits from accounting profits. Accounting profits have clearly risen, but perhaps these profits just represent a higher required return on capital, not an increase in economic profit. This explanation fits well with the observation of a very low savings rate, which makes capital scarce. However, it is not consistent with the observation of a low interest rate. Obviously capital is still cheap for high-quality borrowers like the US government. Why would it be so expensive for businesses?

3. Increasing price of risk. The capital that gets compensated by profits is necessarily high-risk capital. Possibly, even though generic capital is cheap, the risk premium for equity capital has risen: investors have gotten more timid. If we compare today to 2000, this is almost certainly part of the story. But if we compare today to 1990, this argument is less compelling. Overall, price-earnings ratios have risen over the past 15-20 years, and dividend yields have fallen, which suggests people are more, not less, willing to invest in risky assets.

4. Rising rents. Some of what is counted as profits may actually be rents, and those rents may be rising. For example, an oil company that owns mineral rights continues to account for depletion based on original cost, even though the economic value of those rights has risen, so the implied rental cost shows up as profit. You could also argue that firms like Microsoft that own valuable intellectual property are earning large rents on that property, and those rents show up as profits. This explanation is more promising than some of the others. It’s certainly consistent with the observed unevenness of profits across sectors.

5. Reduced competition. Maybe the zero profit condition doesn’t apply any more. It’s hard to think of examples, though.

6. Product and labor market disequilibrium. Over the course of the business cycle, labor costs tend to rise during booms and fall during recessions, whereas prices rise more evenly throughout the cycle and perhaps accelerate before the boom phase is reached. If the Fed’s anti-inflation policies have made recessions more common than booms (“taking away the punch bowl before workers get to drink”), this could explain a shift of income away from labor. If this explanation is right, it bodes badly for profits in the future, because disequilibria tend to get corrected in the long run, no matter what the Fed does.

7. Capital market disequilibrium. Economic liberalization has resulted in a large increase in the effective global labor supply. According to classical economic theory, this should result in a (possibly temporary) increase in the cost of capital, as scarce capital is allocated toward the newly available labor. As noted earlier, observed low interest rates are not consistent with this story, but perhaps allocating capital is more complicated in the short run. Suppose, for example, that firms have a limit on the number of investment projects they can undertake at a given time. Even if capital is cheap, they won’t be able to take full advantage, but those projects they do undertake will be located where the plentiful labor is – i.e., not in the US. Thus the required return for US investments could be quite high (hence high US profits and high prices relative to wages) even if the raw cost of capital is low.

Labels: capital, economics, finance, income distribution, inflation, macroeconomics, profits, US economic outlook, wages