Bubble? No. Crash? Yes.

Listen closely to the US housing market. At first, you may think you hear a hissing sound, but what I hear are the wheels of a moderately efficient market grinding out a new equilibrium price. By my very rough estimate, the fundamental value of the average US house has fallen by about 15% over the past year.

A house represents a stream of housing services, and the value of the house depends on the rate at which you discount those services. Since housing services can also be purchased with money (rent), the discount rate for housing services has to maintain some relationship with the discount rate for money (the interest rate, which, as you may have noticed, has been rising lately).

In a post last year, James Hamilton goes into more detail on the basic mathematics of house pricing and ends up with the formula H = s/(i-g), where H is the house price, s is the value of housing services (rent), i is the interest rate, and g is the growth rate in the value of housing services. In my calculations, I assume that the growth rate is equal to the inflation rate, so the formula simplifies to H = s/r, where r is the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate.

What real interest rate, in particular? There is no easy answer, but to make things simple, I just take the (easily observable) 10-year TIPS yield and add a 2% risk premium. 2% corresponds roughly to the typical spread between 30-year mortgage APRs and 10-year treasury yields. A subtle housing economist would also account for a lot of other details, such as maintenance costs and tax deductions, but I just want to look at the big picture, so I’ll assume that those things net out to zero.

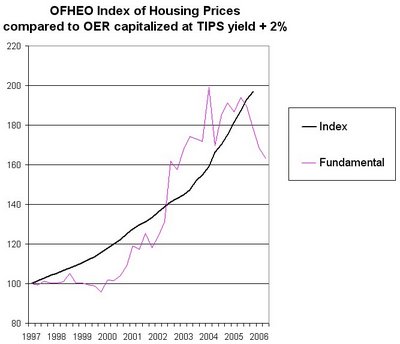

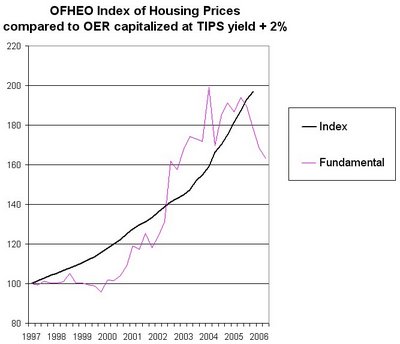

Using the CPI for Owner’s Equivalent Rent, I calculated the path of this “fundamental value” (H) since 1997 (when TIPS were first issued) and compared it to the path the OFHEO house price index. (Both numbers are indexed to start at 100.) The chart below shows the result.

Housing prices did roar ahead of the fundamental during the economic boom of the late 1990s, but with the decline in interest rates starting in 2001, the fundamentals caught up with prices and then pulled ahead. From 2003 to 2005, actual prices were catching up with fundamentals. By the first quarter of 2006 (the last data point from OFHEO), prices were just slightly above the fundamental (not what I would call a bubble!), but in the subsequent two quarters, with interest rates rising, the fundamental has dropped dramatically. As a fundamentalist who never bought the bubble story, I won’t be at all surprised to see housing prices drop (in real terms, certainly, and perhaps in nominal terms as well) over the coming months and years.

A house represents a stream of housing services, and the value of the house depends on the rate at which you discount those services. Since housing services can also be purchased with money (rent), the discount rate for housing services has to maintain some relationship with the discount rate for money (the interest rate, which, as you may have noticed, has been rising lately).

In a post last year, James Hamilton goes into more detail on the basic mathematics of house pricing and ends up with the formula H = s/(i-g), where H is the house price, s is the value of housing services (rent), i is the interest rate, and g is the growth rate in the value of housing services. In my calculations, I assume that the growth rate is equal to the inflation rate, so the formula simplifies to H = s/r, where r is the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate.

What real interest rate, in particular? There is no easy answer, but to make things simple, I just take the (easily observable) 10-year TIPS yield and add a 2% risk premium. 2% corresponds roughly to the typical spread between 30-year mortgage APRs and 10-year treasury yields. A subtle housing economist would also account for a lot of other details, such as maintenance costs and tax deductions, but I just want to look at the big picture, so I’ll assume that those things net out to zero.

Using the CPI for Owner’s Equivalent Rent, I calculated the path of this “fundamental value” (H) since 1997 (when TIPS were first issued) and compared it to the path the OFHEO house price index. (Both numbers are indexed to start at 100.) The chart below shows the result.

Housing prices did roar ahead of the fundamental during the economic boom of the late 1990s, but with the decline in interest rates starting in 2001, the fundamentals caught up with prices and then pulled ahead. From 2003 to 2005, actual prices were catching up with fundamentals. By the first quarter of 2006 (the last data point from OFHEO), prices were just slightly above the fundamental (not what I would call a bubble!), but in the subsequent two quarters, with interest rates rising, the fundamental has dropped dramatically. As a fundamentalist who never bought the bubble story, I won’t be at all surprised to see housing prices drop (in real terms, certainly, and perhaps in nominal terms as well) over the coming months and years.

Labels: data, economics, housing, interest rates, macroeconomics, US economic outlook

4 Comments:

Knzn,

I think I see what you're saying. Most people have to get mortgages to buy house over a period of decades. They are willing to pay a high premium when the interest rate is low because it enable them to lock in a lower rate. And thus when the interest rates is raised, housing prices logically comes down.

All I can say is, that bloodcurdling scream is coming from people who bought near the top of the market with adjustable-rate mortgages.

That’s basically it, but there are a few other important points: (1) Since rents are always expected to rise (because we always have a positive inflation rate), part of the mortgage payment is like an up-front payment to compensate for higher rents that you would have had to pay in the future; that’s why I use a real interest rate. (2) The lower the real interest rate is to begin with, the more impact a change will have on the value of a house (the explanation is too long to go into here); so the fact that interest rates have been quite low recently explains both why housing prices have responded so dramatically to falling rates and why they are likely to respond dramatically to rising rates. (3) The way I think about it, the equity portion of the house is also a factor; for example, even if you bought a house with no mortgage at all, you’d still be willing to pay more when interest rates are low, because the alternative investments are less attractive. (Think, for example, if you had $300,000 lying around, you could buy a bond and use the interest to pay your rent, or you could buy a house and pay no rent, so the interest on a $300,000 bond should approximately equal what you would pay in rent for a $300,000 house – after correcting for inflation, of course.)

Yes, people with ARMs are screwed. To the extent that people have used ARMs to buy houses over the past couple of years, I would say that constitutes a bubble element, or perhaps just plain bad judgment. (I’m puzzled as to why Greenspan seemed to encourage that bad judgement.)

Actually (to amend my previous comment) you could make a case that people who bought with ARMs just had bad luck rather than bad judgment. If you’re buying a house with an ARM, and you want to decide how much the house is worth to you, you need to estimate what your interest rates will be over the life of the loan. One reasonable way to estimate is to look at fixed rates, because fixed rates, at least according to one well-respected theory, represent the market’s expectation for what floating rates will do (plus probably a risk premium). (For example, if investors expected floating rates to rise above current fixed rates, then presumably nobody would be willing to invest at a fixed rate, and the fixed rate would have to rise.) So when you value the house (assuming you believe the expectations theory of the term structure), it doesn’t really matter whether you intend to purchase with a fixed-rate mortgage or an ARM, because your estimate of ARM rates will be similar to what the fixed rate is.

Is it foolish, though, to finance with an ARM, once you’ve decided to buy the house? It isn’t really foolish; it’s just risky. Since most economists believe that fixed rates include a risk premium, the chances are you would end up paying less with an ARM than with a fixed rate mortgage, so there is a good reason you might choose an ARM. But chances are chances, and if you took that chance in, say, 2004, even though it might have been a good bet, it didn’t end up paying off. (Actually, the game isn’t over yet; it may yet pay off.) Obviously, if you’re the kind of person who likes to play it safe, getting an ARM is not a reasonable thing to do. But if you’re willing to take risks, you need to be willing to accept that those risks sometimes don’t pay off.

酒店喝酒,禮服店,酒店小姐,酒店領檯,便服店,鋼琴酒吧,酒店兼職,酒店兼差,酒店打工,伴唱小姐,暑假打工,酒店上班,酒店兼職,ktv酒店,酒店,酒店公關,酒店兼差,酒店上班,酒店打工,禮服酒店,禮服店,酒店小姐,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店經紀,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店小姐,台北酒店,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店小姐,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店小姐,禮服店 ,酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店小姐,酒店傳播,酒店經紀人,酒店,酒店,酒店,酒店 ,禮服店 , 酒店小姐,酒店經紀,酒店兼差,暑假打工,招待所,酒店小姐,酒店兼差,寒假打工,酒店上班,暑假打工,酒店公關,酒店兼職,禮服店 , 酒店小姐 ,酒店經紀 ,酒店兼差,暑假打工,酒店,酒店,酒店經紀,酒店領檯 ,禮服店 ,酒店小姐 ,酒店經紀 ,酒店兼差,暑假打工, 酒店上班,禮服店 ,酒店小姐 ,酒店經紀 ,酒店兼差,暑假打工, 酒店上班,禮服店 ,酒店小姐 ,酒店經紀 ,酒店兼差,暑假打工, 酒店上班,酒店經紀,酒店經紀,酒店經紀

Post a Comment

<< Home