Not a Bubble

The clear implication of the chart is that normal prices are around an index value of 110, the value that reigned for nearly fifty years (circa 1950-1997). So if the massive run-up in house prices since 1997 [culminating at an index value around 200] was a bubble and if the bubble has now been popped we should see a massive drop in prices.As Battlepanda points out, "Do you?" is not a very convincing argument unless you already agree with him. But I think I can make it a little bit more convincing:

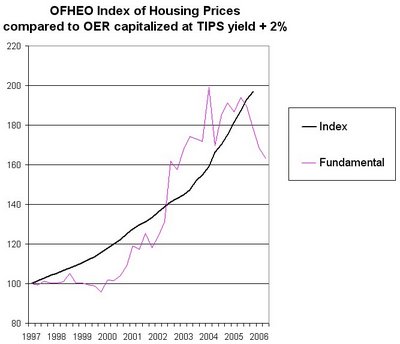

But what has actually happened? House prices have certainly stopped increasing and they have dropped but they have not dropped to anywhere near the historic average. Since the peak in the second quarter of 2006 prices have dropped by about 5% at the national level (third quarter 2007). Prices have fallen more in the hottest markets but the run-up was much larger in those markets as well.

Prices will probably drop some more but personally I don't expect to ever again see index values around 110. Do you?

Prices will probably drop some more, but personally, given the likely effect that an additional 40% drop in home prices would have on the already weak economy, I don't expect that the Fed will allow index values to fall to anywhere near 110 in the foreseeable future. Do you?Some people will respond with something like, "OK, I don't either, but that doesn't mean it wasn't a bubble; that just means there's a Bernanke put on home prices: there was a bubble, and the Fed is now going to ratify the results of the bubble." But that's not right. The Fed is not actively causing inflation in order to bail out homeowners and their creditors. The vast majority of professional forecasts call for the inflation rate to fall over the next few years. The Fed is just doing its job -- trying to keep inflation at a low but positive rate while maximizing employment subject to that constraint. The ultimate concern of the Fed is to avoid deflation, which becomes a serious risk if the US housing market has a total meltdown. It's very much as if the Fed were passively defending a commodity standard, with the core CPI basket as the commodity.

The ultimate source of the housing boom is the global surplus of savings over investment. That surplus is what pushed global interest rates down and thereby made buying a house more attractive than renting. And that surplus is still with us. If anything, it appears to be getting worse, as US households begin to reject the role of "borrower of last resort." And it is that now aggravated surplus that threatens us with weak aggregate demand and the risk of economic depression in the immediate future -- a risk to which the Fed and other central banks will respond appropriately. Until the world finds something else in which to invest besides American houses, the fundamentals for house prices are strong -- not strong enough, probably, to keep house prices from falling further, but strong enough to keep them well above historically typical levels.

Labels: Bernanke, deflation, economics, housing, inflation, interest rates, macroeconomics, monetary policy, US economic outlook