Bad Luck

Under the Keynesian paradigm, a loose policy can be defined as one that tends to push the unemployment rate below the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), so that inflation will tend to accelerate. Conversely, a tight policy can be defined as one that tends to push the unemployment rate above the NAIRU, so that inflation will tend to decelerate. Whether the unemployment rate is in “loose” or “tight” territory, the economy will be subject to shocks (bad luck – or good luck), which may cause the inflation rate to do something else, but these shocks cannot be blamed on (or credited to) policy. (Also, there may be shocks in the policy transmission process that prevent the unemployment rate from reaching its intended level in the first place, but these aren’t the type of shocks that people have in mind when discussing the 1970s.)

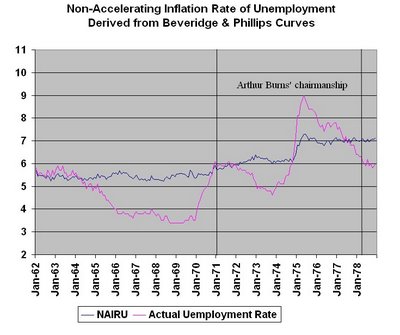

The average unemployment rate for the US during the 1970s was 6.2%. Until the mid-1990s, conventional estimates put the NAIRU at about 6%. Using the conventional linear approximation to the Phillips curve, this means that policy, on average, managed to push the unemployment rate to a level that should have resulted in a slight decline in the inflation rate. On average, policy was tight, not loose.

If anything, this simple analysis underestimates the extent to which policy was tight. The 6% NAIRU estimate came with full benefit of hindsight. An estimate produced using data available during the mid-70s would put the NAIRU somewhat lower. So if we describe policy in terms of its actual intentions, rather than the results that might have been anticipated with benefit of hindsight, it was more than a little tight.

This is not to say that policymakers (meaning the Fed) necessarily acted appropriately during the 1970s. Perhaps, in the interest of restoring the credibility they lost during the Johnson-Nixon years, they should subsequently have been even tighter than they were. Perhaps high inflation is just bad and should have been met aggressively at every turn, even when it was not the result of recent policy. But leaving these normative issues aside, it’s hard (at least if we accept the Keynesian paradigm) to see how, in the absence of considerable bad luck, the inflation rate at the end of the 1970s could have been so much higher than it was at the beginning. Did anyone notice a black cat on Constitution Avenue?

Labels: Burns, economics, inflation, macroeconomics, monetary policy, NAIRU, Phillips curve, unemployment